- Home

- David Free

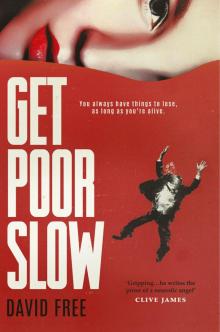

Get Poor Slow

Get Poor Slow Read online

About Get Poor Slow

‘Gripping . . . he writes the prose of a neurotic angel’ Clive James

By forty you’re meant to have the face you deserve. I got the face early. It took me a while to earn it. I believe I am finally there.

Ray Saint is in trouble. A young woman is dead and he was the last person to see her alive. No one is impressed by his excuses: Ray, you see, is the most hated book reviewer in Australia – a hatchet man with a belly full of bourbon and curdled dreams of literary greatness. Now he will need all of his acid-tongued wit and even some moments of lucidity if he is to discover who murdered the beautiful publishing assistant who got so far beneath his skin.

As a battered and bloodied Ray investigates more deeply, he is obliged to face the truth: he can’t be entirely sure that he isn’t the killer.

‘My favourite Australian literary critic, David Free instantly becomes my favourite Australian author of psychological thrillers, with this gripping tale of a literary man thoroughly screwed up by sexually intriguing women and crazy editors. Free is far too civilized for this kind of thing, which is probably why he’s so disturbingly good at doing it.’ Clive James

Contents

Cover

About Get Poor Slow

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

About David Free

Copyright page

For my family,

and in memory of my mother

1

I’m starting to doubt this thing will end soon. Last night one of them came up to the house. I was inside, doing what I do these days when it gets dark. No lights on, no book, no TV, no sounds, just a glass in my fist with not much left in it. For some reason I was on my feet, walking past the big side window, when a whisper of movement beyond the pane made me halt and turn. And there the fucker was, standing out in the rain. At first I thought he was me. I thought I was looking at my own reflection: a trick of moonlight on glass. Then I raised my arm to take a drink and he didn’t raise his. That was a worry, but I took the drink anyway. There was more light out there under the moon than there was in the house. We looked at each other for what seemed a while. I was drunk, which wasn’t helping. If I’d said something to him he’d have heard it through the glass, but I could think of no quip equal to the occasion. One of us was in the wrong and I doubted for once it was me. He reached down for something near his waist. I thought: this is probably it. I’m about to get shot. I had time to work out I wouldn’t mind that very much. At least it would change things, one way or another. Then he brought the thing up to his face, and in the light of its flashes I saw what it was.

There’s a way such scenes are meant to play out, in the age of the image. The infamous man is meant to stride towards the lens, hands raised into the storm of light, grimly primed to fuck up the other guy’s camera or face or both. Out in the rain, the other guy seemed put out that I wasn’t doing these things already. He’d got his shots, but he wasn’t leaving. It was my turn to move, and movement has sort of stopped being my thing. I have this strange inertia these days. My tastebuds are all shorn off, and the world feels bleached-out, as if every day is the day after someone has died. But I wanted him gone. So I played my part, I drifted with the tide, which is another thing I seem to do now. I went for the front door. Beyond its stippled glass panes his volleys of light started up again, bursting like flak. He was moving back across the deck to the front steps. He looked washy and deformed through the glass, a lean nocturnal fiend supplying his own lightning. By the time I yanked the door open he was jogging down the dark steps, the tethered camera lolling around his waist. I didn’t bother going after him. I walked out to the deck’s edge and watched him trot away down the dirt drive. When he looked back through the weak wet moonlight and saw I wasn’t coming, he stopped trotting and slowed to an insolent stroll. That bothered me. At last I mustered some outrage. The heavy tumbler in my hand was still half-full. I drained it in one go, as if biting the pin from a grenade, then hurled it high into the night. When it was somewhere near the peak of its arc I stopped hoping it would hit him. Maiming a journalist would be fun for about two minutes. Then it would start being one more thing I can’t live down. Anyway it missed him. It hit my car instead. I heard the sound of glass bursting and hollow bodywork taking a deep dent: the sound of my life getting worse than it already was. Beyond the car, in the sheltering night, the photographer laughed. Then I wished I’d nailed him. He was down at the haven of the front gate now: out where all the vans are parked, with the logos of the TV networks stencilled expensively on their sides.

There are headaches so foul they pollute your sleep. I’ve forgotten what the other kinds are like. Even in my dreams I want to ram my skull through a sheet of plate glass to get relief. Bad tunes get stuck in my head and go round and round, their needle jammed deep in the melting shellac of my brain. I was dreaming she wasn’t dead. We were talking. I couldn’t hear what she was saying but that didn’t matter. The point was that she was there. She had never gone away.

And then I had that moment of freefall when the dream is over but reality still hasn’t kicked in. In that moment I still wasn’t me and she still wasn’t gone. And then I landed, and the truth lunged back into my head for another day, like a fat bandit vaulting the counter of a convenience store. I half-opened my eyes, and got a ruinous blast of morning light. I wasn’t in my bed. I was on the couch. The phone was ringing. I shut my eyes again. You never know whether to open them or keep them closed. Each thing feels worse than the other while you’re doing it. There was a coffee table to my left. I thought maybe there was something medicinal on it. Sometimes, the night before, I have the wit to lay out a care package for the morning after. I eased sideways to check. That made a fistful of small but solid objects slide off my chest and rain down on the hard wooden floor. Harmonicas. What a bad sign that was. Apparently I’d felt pretty good during the night. I had not acted in moderation. While my life burned, I’d lain there in the dark like Nero, playing the blues in multiple keys.

I sat up. The fire in my skull took a smudged moment to follow, slopping around in my wake like a shouldered sack of trash. Half-blind in the light, I squinted at the clock and hated what it said. I got up and made it to the sink by feel. The room isn’t big, and there’s not much to run into on the way. The phone was still ringing. At the sink I opened my eyes again, but not by much. Looking at things hurt. I reached for a bottle of what turned out to be olive oil. I didn’t find that out by drinking it, but I got close. When I found the bottle I wanted I took a restrained lash of its heat. Restrained was the last thing I felt like being, but I had to go out in public today. I had to drive. I had to perform. From my uppermost cupboard I pulled down my war chest and dealt myself a wretched hand of blister packs: a pair of twos, a three, a five. I thumbed out pills. One pill I thumbed too keenly: it crumbled like plaster and sprayed to the floor. That put me down on my knees for a while, eating bitter white dust off the wood with a wet finger. I felt relatively okay down there. I wanted to rest my skull on the cold boards and stay there all day. But in ninety minutes I was due down in the vile city again, to assist Ted Lewin with his inquiries. I needed to be at my least bad for that. Nimbleness would be required. A line had to be trod. I didn’t want to assist him too much. He was doing a solid enough job on his own. But assisting him too li

ttle was starting to be no good either. It was doing bad things to our relationship.

Back on my feet, I tried hard not to look again at that bottle of oil. Overnight, in the cold, the stuff inside it had gone all white and lardy. It reminded me of pornography, and pornography reminded me of her. There were ghosts everywhere, and she was all of them. I cracked a final pill from its cocoon and rolled it between my fingers and thumb. I was in two minds about putting it in my mouth. It was a gel cap, half-red, half-white. It was tubular and nasty, like a rifle slug. And it would work like a bullet too, if I took it. When it blew away the pain, it would blow away half my wits and motor skills with it. Going into Lewin’s miked-up room in that state was semi-unthinkable, but so was going in there the way I felt now. For a while I got stuck on the paradox and just stood there at the sink, not moving. Tumbleweeds of razor wire clashed in my skull. Finally my hand got sick of waiting and made a rogue move to cram the pill into my mouth. It didn’t work. My fingers twitched and botched the execution. The capsule hit my lip and dropped to the counter and rolled. I threw my other hand at it. That sideswiped it into the sink, which had been full of dirty water for exactly as long as she had been dead. The water was thick and oyster-grey. Pale blooms of scum or ice or lichen were floating on its surface. I plunged my hands through them. My forearms burned from the cold. The gel wouldn’t last long down there. The longer it stayed under, the worse it was going to taste when it came up. If it was any other pill I’d have let it drown. But a box of red-and-whites costs more than I get paid for a book review. I frisked submerged steel. My fingers were slick with grease. I pulled up a few things that weren’t the pill. By the time I found the real thing it had the texture of a flagging hard-on. I swallowed it before I could decide not to. Tasting it gave me a solid excuse to take one more mouthful of bourbon. It tasted better than the sink water, but not by much. The day I start liking the taste of it will be the day I’m really in trouble.

I put on coffee. The phone was still ringing. I still didn’t pick it up. I went to the front window and pulled back the edge of the curtain. The light lanced into my eyes and buried itself hilt-deep in my skull. Down at the front gate, where my dirt drive met the steep scrappy road, the big vans were still parked. They were from rival networks, but their crews stood together in one big chummy gang, breathing vapour into the dawn, a gaggle of drooling villagers waiting for the monstrous common enemy. Instead of pitchforks they had boom mikes on sticks. Instead of flaming torches they had steaming cardboard cups. The girl reporters wore big unsexy parkas. Sticking out from underneath was the stuff they would wear on camera: short skirts, dark stockings, high heels. One of them saw me at the window. She rapped the shoulder of the guy next to her and pointed. I let the curtain drop.

I sat there on the curtain’s safe side and drank coffee till my breath tasted of that and not booze. I do not get headaches because I drink. I drink because I get headaches. If you don’t get the difference, leave now. On mornings like this one, the crack in my skull feels blazingly reborn. It feels as if it got put there overnight. I feel thick hot blood raging inside it like lava. The pain detaches me from the here and now. I rarely feel present in my own life. If it’s not the pain, it’s the stuff I take to get rid of it. And now there is the fog of the other thing too, her, hanging over the world like a sick scuzzy moonlight that won’t go away.

The phone started ringing again. I hadn’t noticed it had stopped. This time I decided to pick it up. It couldn’t be worse than listening one more time to its endless bitter skirl.

‘You dog,’ a man’s voice said. ‘You sick, sick cunt. You’re a dead man.’

‘Come and do it,’ I urged him.

He said a few more things. I hung up. I’d got his gist.

I poured more coffee. I have a mashed nose and a limited sense of smell, but even I can tell that the house is starting to stink of garbage. I’ve grown wary of putting things out at the kerb. I have become ashamed of my trash. A week ago I put out a crate of empty bottles. It wasn’t even a big crate, as crates go. And the next day, down at the gate, I got questions about my drinking. I answered them with a fair bit of candour. I was a novice in those days. I still believed that the truth, or part of it, would set me free. I told them I drink so I can feel as good as everyone else feels when they don’t drink. I told them my idea of fun would be never having to drink again. I tried hard to evoke my drinking’s nuances. I told them about my accident, my head hitting the ground. I told them the details would bore them – the way they bore my expensive doctors, the way they bore me.

And that night the TV started saying I had a drinking problem. A psychologist came on and dropped dark hints about the lingering effects of head trauma. And I hadn’t even told them the whole truth. Just a bit of it. And how sinister this fragment had made me seem, how abnormal. If you can’t tell them everything, tell them nothing. Under a big enough spotlight, any life will start to look sordid. I’m still learning these things. My life used to be nobody’s business except mine. Now it’s everyone’s except mine.

In the bathroom I ran water for a shave. I told myself that things weren’t out of control yet. They just felt as if they were. I could still pull the ripcord whenever I liked. I am the author. I know things other people don’t. Even Lewin. Especially Lewin. I know things he doesn’t, and it would be rash to give up that edge too early. Then again, there is such a thing as waiting too long. Ripcords don’t work after you hit the ground.

I got dressed. I wear what people expect a literary critic to wear: black jeans, black boots, a brown jacket over a grey shirt. It’s the only respectable outfit I own, and I have reason to fear that it’s starting to stink too, like everything else. In truth, literary critics don’t dress like this. They stay home and write, wearing pyjamas. They don’t shave. But suddenly I am a public man. I have an impression to make – or an impression to rectify, fast. People know who I am now, and I’m running out of time to make them think I’m someone else. When the first photo of me appeared in the newspaper, the headline said: The Face of Evil? You had to love that question mark.

I was running late. I filled a flask and slid it into the pocket against my heart. In the pocket on the other side I stashed a deck of foils and a small vessel of mouthwash. Everything I need to get through a day can still be discreetly carried on my person, as long as the day is only half a day long.

I locked the front door and went down to the car. In the slab of shadow cast by the house, the clumpy grass was still rimed with frost. The car still had shards of last night’s tumbler on it. I swept them off and drove down to the gate. There I stopped the car but not the engine. I rolled my window down. And here they came, eclipsing the winter sun: the girl reporters losing the heavy jackets, the rolling scrum of branded mikes and lofted smart phones. Tedious as these scenes are, they must be played out. Not stopping for them feels good, until you see what it looks like on the news: your furtive car slinking past them, your smudged sinister form behind the glass. And them on their side of it, yelling the question at their own guiltless reflections. That looks bad. Even I can see that.

‘Did you murder Jade Howe?’ one of them now shouted.

‘No,’ I told her.

How many times do I have to say it? How many times do they have to film me saying it? Answer: one time a day for each different network. Every morning every last girl must ask it afresh, as if she’s never asked it before – as if this time she will shock me into uttering the truth. If the camera doesn’t get her the first time, she will ask again. And I must respond calmly, without boredom, every time – unless I want discourtesy added to the list of my sins.

‘There’ve been reports,’ said someone else, ‘that your fingerprints were found in her bedroom.’

‘I hadn’t heard that,’ I said.

‘Mr Saint, did you murder Jade Howe?’ another girl said.

‘No I did not.’

The trick is to

keep things flat, stripped of highs and lows. My worst moment of the morning will reliably feature as that night’s money shot. All I can do is make sure the worst is not too bad.

‘Why were your fingerprints in her house?’ somebody else said.

‘Because I was in there once,’ I said, ‘when she was alive.’

‘In her bedroom?’ someone said lewdly.

The guy from last night was back there on the fringe of the crowd, holding his camera over the pack like a priest lofting a censer. How many more shots of me does this guy need? Are there still people left who don’t know what I look like?

‘Wasn’t she a bit young for you, Mr Saint?’ said someone else.

I said, ‘End of press conference.’

Detective Inspector Ted Lewin’s eyeballs do not match. One of them is damaged or malformed. Violence has been done to the iris: the brown of it has oozed out beyond its natural circumference, like the broken yolk of an egg. When I have cause to look him square in the eye, I never know which eye to look square at. I don’t have cause to all that often. When I get the chance, it would be nice to know the effect is not going to waste.

‘I’m the last bloke on this case who thinks you didn’t do it,’ he told me this morning.

‘Last week you were the second-last.’

‘Well,’ he said, ‘this has been a bad week for you.’

The room in which I assist him with his inquiries is small. Nothing in it is designed to make you want to stay. There are no windows. Everything except the furniture is clinic-white: the floors, the walls, the panels of the ceiling, the strip lights. You can catch yourself thinking that nothing you say in there will matter in the world outside. You can catch yourself forgetting that there is a world outside. We sit on plastic chairs and face each other. For the first two sessions Lewin worked in tandem with some other guy, a mute sidekick. Now we convene alone – as if the other guy was the problem. I do my best to keep my body language open and relaxed. A laminated table stands to one side of us. On Lewin’s end there is a stack of stuffed manila folders that gets closer to the ceiling each week. Above us, in the room’s top corners, there are dark plastic bulbs housing digital cameras you can neither see nor hear. The air smells of nothing. It has a zero-gravity feel. In the sterile cube of that room, the nuanced answer goes down no better than it does at my press conferences. You are either one thing or the other in there: clean or dirty, guilty or innocent. You either have nothing to hide or everything to hide. Who are the people who meet this room’s standards? They must have no secrets at all. They must be able to lay out their full life stories without hesitation or shame. Lewin seems like the kind of man who could do that. I’ve never heard him raise his voice. He doesn’t swear. He keeps the temperature of things low. He talks about her dead body without passion. For him, her death is a given, a problem that can and will be solved. All he wants from me is the truth, pure and simple. Oscar Wilde had an answer for that. The truth is rarely pure and never simple. And look at what happened to him.

Get Poor Slow

Get Poor Slow